BBC Earth

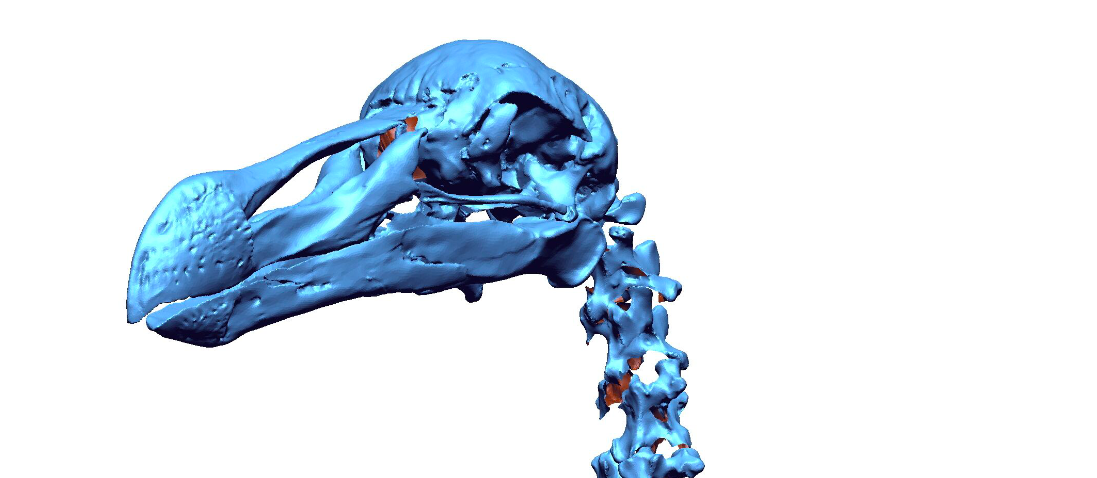

Image: L. Claessens

Most people are familiar with the sad story of the dodo. This plump, flightless bird was so tasty and so tame that it was hunted to extinction within a century by Dutch sailors arriving on the shores of Mauritius.

Rather fewer people realise that this story is largely incorrect.

Tasty? Apparently not – the waste pits from the early Mauritian settlements, which were excavated for a study published in 2013, are full of animal bones from the Dutch dinner table, but there is not a single dodo bone amongst them.

Hunted to extinction? Unlikely – Mauritius was blanketed in thick impenetrable rainforest, and dodos deep in the heartland would have been well beyond the reach of even committed hunters.

Plump? No – the tubby bird depicted in modern reconstructions is based on illustrations probably drawn from overfed captive birds or poorly-stuffed dead specimens. In the wild the dodo was a much leaner bird.

How can such an icon of human-induced extinction be so misunderstood? The answer lies in the shameful way the dodo has been treated since the last bird died about 350 years ago. Arguably, we have lost the dodo at least twice more since then.

“We have this continuous series of tragedies, forgetting the dodo over and over again,” says Leon Claessens at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts.

But perhaps no longer. Because of the work of Claessens and his colleagues – including Julian Hume at London’s Natural History Museum and Kenneth Rijsdijk of the University of Amsterdam – science is finally giving the dodo the attention it deserves. Read more on the BBC Earth website…