New Scientist

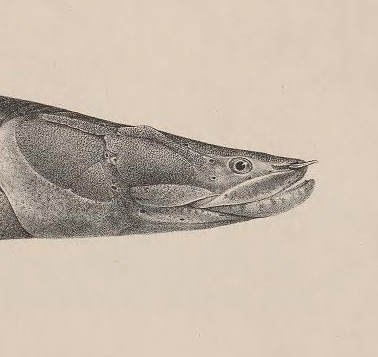

Image: BioDivLibrary

“To be honest, I was intrigued to see if they’d even survive on land,” says Emily Standen. Her plan was to drain an aquarium of nearly all the water and see how the fish coped. The fish in question were bichir fish that can breathe air and haul themselves over land when they have to, so it’s not as far-fetched as it sounds.

What was perhaps more questionable was Standen’s rationale. Two years earlier, in 2006, Tiktaalik had become a global sensation. This 360-million-year-old fossil provides a snapshot of the moment our fishy ancestors hauled themselves out of the water and began trading fins for limbs. Standen thought forcing bichir fish to live almost entirely on land could reveal more about this crucial step in our evolution. Even if you were being kind, you might have described this notion as a little bit fanciful.

Today, it seems positively inspired. The bichirs did far more than just survive. They became better at “walking”![]() . They planted their fins closer to their bodies, lifted their heads higher off the ground and slipped less than fish raised in water. Even more remarkably, their skeletons changed too. Their “shoulder” bones lengthened and developed stronger contacts with the fin bones, making the fish better at press-ups. The bone attachments to the skull also weakened, allowing the head to move more. These features are uncannily reminiscent of those that occurred as our four-legged ancestors evolved from Tiktaalik-like forebears. Read more on newscientist.com…

. They planted their fins closer to their bodies, lifted their heads higher off the ground and slipped less than fish raised in water. Even more remarkably, their skeletons changed too. Their “shoulder” bones lengthened and developed stronger contacts with the fin bones, making the fish better at press-ups. The bone attachments to the skull also weakened, allowing the head to move more. These features are uncannily reminiscent of those that occurred as our four-legged ancestors evolved from Tiktaalik-like forebears. Read more on newscientist.com…