New Scientist

Image: PROYECTO AGUA** /** WATER PROJECT

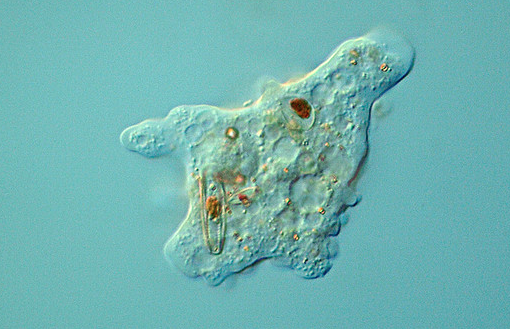

Amoebas are smarter than they look, and a team of US physicists think they know why. The group has built a simple electronic circuit that is capable of the same “intelligent” behaviour as Physarum, a unicellular organism – and say this could help us understand the origins of primitive intelligence.

In recent years, the humble amoeba has surprised researchers with its ability to behave in an “intelligent” way. Last year, Liang Li and Edward Cox at Princeton University reported that the Dictyostelium amoeba is twice as likely to turn left if its last turn was to the right and vice versa, which suggests the cells have a rudimentary memory.

This year, Toshiyuki Nakagaki at Hokkaido University in Sapporo, Japan,won an Ig Nobel prize for his work on amoeba intelligence after his team found further evidence of the amoeba memory effect. They exposedPhysarum amoeba to temperatures fluctuating regularly between cold and warm. It was already known that the cells become sluggish during cold snaps, but Nakagaki’s team found that the amoeba slowed down in anticipation of cold conditions, even when the temperature changes had stopped (Physical Review Letters, DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.018101).

Massimiliano Di Ventra, Yuriy Pershin and Steven La Fontaine at the University of California, San Diego, wondered what was responsible for that behaviour.

Amoebas are smarter than they look, and a team of US physicists think they know why. The group has built a simple electronic circuit that is capable of the same “intelligent” behaviour as Physarum, a unicellular organism – and say this could help us understand the origins of primitive intelligence.

In recent years, the humble amoeba has surprised researchers with its ability to behave in an “intelligent” way. Last year, Liang Li and Edward Cox at Princeton University reported that the Dictyostelium amoeba is twice as likely to turn left if its last turn was to the right and vice versa, which suggests the cells have a rudimentary memory.

This year, Toshiyuki Nakagaki at Hokkaido University in Sapporo, Japan,won an Ig Nobel prize for his work on amoeba intelligence after his team found further evidence of the amoeba memory effect. They exposedPhysarum amoeba to temperatures fluctuating regularly between cold and warm. It was already known that the cells become sluggish during cold snaps, but Nakagaki’s team found that the amoeba slowed down in anticipation of cold conditions, even when the temperature changes had stopped (Physical Review Letters, DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.018101).

Massimiliano Di Ventra, Yuriy Pershin and Steven La Fontaine at the University of California, San Diego, wondered what was responsible for that behaviour. Read more on newscientist.com…