New Scientist

Image: sigurdga

The Dahshur royal necropolis in Egypt was once a dazzling sight. Some 30 kilometres south of Cairo, it provided King Sneferu with a playground to hone his pyramid-building skills – expertise that helped his son, Khufu, build the Great Pyramid of Giza. But most signs of what went on around Dahshur have been wiped away by 4500 years of neglect and decay. To help work out what has been lost, archaeologists have turned to fractals.

All around the world, river networks carve fractal patterns in the land that persist long after the rivers have moved on. “You can zoom in as much as you like, at each magnification the [natural fractals] would look the same,” says Arne Ramisch at the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research in Potsdam, Germany. This should be the case around Dahshur, because it sits on the fringes of the Western desert, where river channels drain into the floodplain of the Nile – but it isn’t.

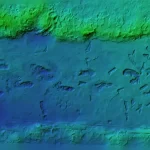

Ramisch and his team generated a digital model of the topography around Dahshur and assessed its fractal geometry as part of their archaeological investigations. They found a surprisingly large area around the pyramids – at least 6 square kilometres – where the natural fractal geometry was absent. The find suggests that the entire area was once modified, probably under the orders of Sneferu and other pharaohs of the Old Kingdom (Quaternary International, DOI: 10.1016/j.quaint.2012.02.045). Read more on newscientist.com…